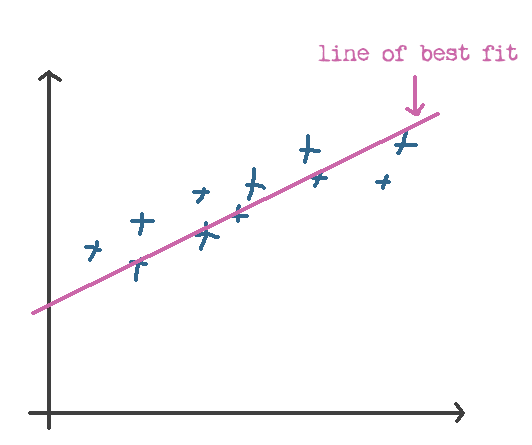

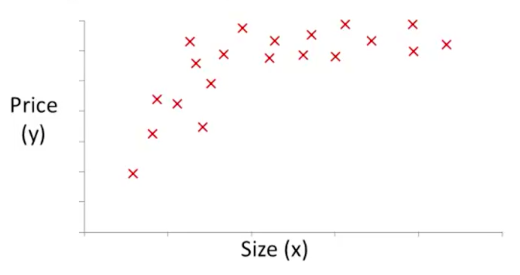

Here’s the deal. So far, we’d only discussed the most basic possible example: a case where you had:

- a single feature (our \(x\), the area of the house)

- a single output (our \(y\), the price of the house)

- and a linear relationship between the two

Now, we’re about to grow up .. because in the real world, we don’t just have a single feature. We have many .. sometimes even thousands!

Think about it .. it sounds absolutely absurd that you would even think that it’s possible to accurately predict the price of a house based on area alone! So many other things matter, like the number of rooms, the floors, the size of the garden, how old it is and it’s sentimental value to you (actually, scratch that last one).

So that’s what we’ll be covering in this post .. how to consider a more complex prediction example.

Don’t forget our goal .. we’re still trying to come up with a hypothesis function that would allow us to accurately predict the price of the house, based on the inputs we’re given.

Let’s do this.

Revisiting our (now broken) equations

We’re going to have to go back and fix the equations we discussed earlier. The definitions (or rather, the meaning) of the equations won’t change .. but we no longer have just one \(x\) to deal with.

First, a few new definitions.

Since we have many \(x\)’s now, let’s give them subscripts (e.g. \(x_1, x_2, x_3\)) to refer to our different features.

Note that we already said that the bracketed-superscripts for \(x\) (like \(x^{(1)}, x^{(2)}\), etc.) represent samples in the training set. This still holds true. We just have to get used to seeing things like \(x_1^{(2)}\), which is the second row (or data point in our training data) of the first feature.

We also need a way to refer to the total number of features we’ve got .. let’s go ahead and call that \(n\).

Now that we have that out of the way, let’s take a look at those equations .. starting with our hypothesis \(h_0(x)\).

Hypothesis function \(h_\theta(x)\)

Before (we had only one \(x\)):

\(h_\theta(x) = \theta_0 + \theta_1 x\)

After (we have many \(x\)’s):

\(h_\theta(x) = \theta_0 + \theta_1 x_1 + \theta_2 x_2 + \text{...}\)

You’ll notice something going on here .. all the terms have both \(\theta\)’s and \(x\)’s .. except for that first one, the lonely looking \(\theta_0\). To simplify things, let’s go ahead and give it an \(x_0\) that has a value of 1 (so that it doesn’t change the equation in any way).

Now, it looks like:

\(h_\theta(x) = \theta_0 x_0 + \theta_1 x_1 + \theta_2 x_2 + \text{...}\)

(where \(x_0=1\))

Let’s take the next jump .. let’s lump up all of those \(\theta_0, \theta_1, \theta_2\), … parameters into a single vector like so:

\[\theta =

\begin{bmatrix}

\theta_0 \\

\theta_1 \\

\theta_2 \\

\vdots \\

\theta_n

\end{bmatrix}\]

.. and similarly ..

\[x =

\begin{bmatrix}

x_0 \\

x_1 \\

x_2 \\

\vdots \\

x_n

\end{bmatrix}\]

Those weird looking towers are known in the mathematics parlance as matrices. If you have no idea what those are, you can think of them as layers of numbers, not very different from your good ole’ Big Mac. If you want to learn more, just check out this video here. You may or may not remember that a matrix with just one column is known as a vector.

So here, we’re treating our \(\theta\) and our \(x\) as a single vector, as opposed to many tiny numbers with little subscripts.

So now, our new hypothesis equation will simply be:

\[h_\theta(x) = \theta^T x\]

That weird looking T on top of the \(\theta\) is known as the transpose of \(\theta\), or \(\theta\) flipped on it’s side like so:

\[\theta^T =

\begin{bmatrix}

\theta_0 & \theta_1 & \theta_2 & \cdots & \theta_n

\end{bmatrix}\]

The reason we use \(\theta^T\) and not \(\theta\) is so that the multiplication will work (if you don’t know how to multiply matrices, check out this short video for a primer).

We now have a new equation for our hypothesis function! (keeping in mind that \(x_0=1\) or this whole business just won’t work).

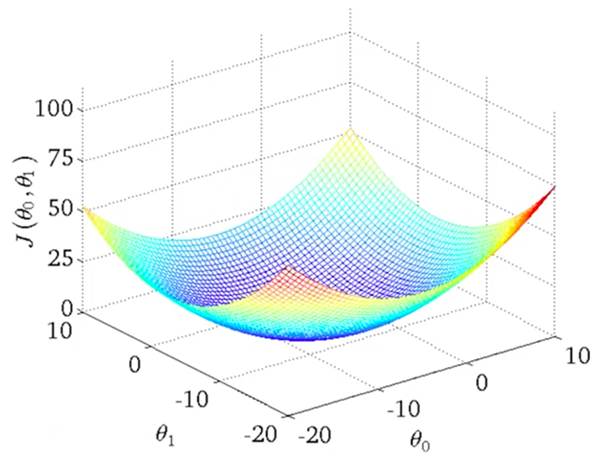

Cost function \(J(\theta)\)

Our new and improved cost function now looks like this:

\[J(\theta) = \frac{1}{2m} \sum_{i=1}^m \left(\ h_\theta(x^{(i)}) - y^{(i)} \right)^2\]

Next, let’s take a look at our gradient descent equation.

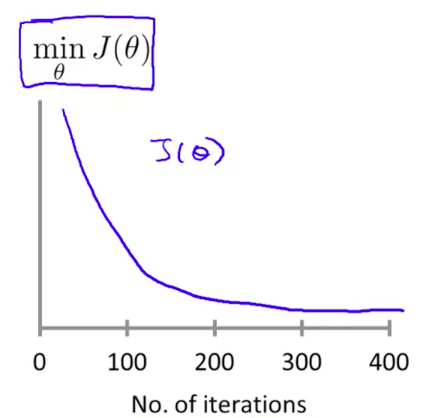

Gradient descent

If you’ll recall, the gradient descent equation in the case of a single feature looked like this:

\[\theta_j := \theta_j - \alpha \frac{\partial}{\partial \theta_j} J(\theta)\]

Substituting for \(J(\theta)\), that becomes:

\[\theta_j := \theta_j - \alpha \frac{\partial}{\partial \theta_j} \left( \frac{1}{2m} \sum_{i=1}^m \left( h(x^{(i)}) - y^{(i)} \right)^2 \right)\]

We then computed the partial derivative for each of our \(\theta_0, \theta_1\) individually, resulting in:

\[\begin{align}

\theta_0 & := \theta_0 - \alpha \frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^m \left(h(x^{(i)}) - y^{(i)}\right) \\

\theta_1 & := \theta_1 - \alpha \frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^m \left(h(x^{(i)}) - y^{(i)}\right) x^{(i)}

\end{align}\]

When replacing this with multiple features, my expectation was that things would get ickier .. much ickier. In fact, I was pleasantly surprised to realize that it wasn’t the case at all.

A fundamental property of partial derivatives is that you only calculate the derivative with reference to the variable you’re deriving with (which are our \(\theta_0, \theta_1\), etc. variables).

Since we’re only going to be computing the derivative with respect to one of these variables at a time, the resulting derivative looks just like the \(\theta_1\) term above.

Namely, it’ll be:

\[\begin{align}

\theta_0 & := \theta_0 - \alpha \frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^m \left(h(x^{(i)}) - y^{(i)}\right) \\

\theta_1 & := \theta_1 - \alpha \frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^m \left(h(x^{(i)}) - y^{(i)}\right) x_1^{(i)} \\

\theta_2 & := \theta_2 - \alpha \frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^m \left(h(x^{(i)}) - y^{(i)}\right) x_2^{(i)}

\end{align}\]

Not too bad, huh?

All the equations look similar except for the first one. Wait .. remember that lonely \(x_0=1\) we were talking about earlier? Well, turns out it’s their in that first equation .. but we just didn’t see it (since it’s equal to 1):

\[\theta_0 := \theta_0 - \alpha \frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^m \left(h(x^{(i)}) - y^{(i)}\right) x_0^{(i)}\]

Now let’s write it in the general form:

\[\theta_j := \theta_j - \alpha \frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^m \left(h(x^{(i)}) - y^{(i)}\right) x_j^{(i)}\]

Kill the feature subset (represented by the subscript \(j\), since \(\theta\) is a vector anyway) and we’re left with:

\[\theta := \theta - \alpha \frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^m \left(h(x^{(i)}) - y^{(i)}\right) x^{(i)}\]

I don’t know about you but I’m feeling like I’ve had my fair share of math for now .. let’s jump into some good ole’ fashioned code.

Implementing things in code

Alright, enough of this math business .. let’s take a look at some code. I’ll be using Octave in this example, since that’s what the Machine Learning course uses (and it makes dealing with matrices, as well as all the rest of the Machine Learning stuff pretty easy).

So yeah, Octave. The syntax is pretty self-explanatory, though writing it will take a bit of getting used to (at least for me anyway).